URL Shortener System Design

A URL shortener is a service that takes a long, complex URL and converts it into a short, easy-to-share link. For example:

https://www.example.com/products/category/item?id=12345&ref=abcdbecomes →https://bit.ly/xyz123

Common URL shortening services include:

- Bitly —

bit.ly/abc123 - TinyURL —

tinyurl.com/xyz789 - Twitter’s t.co (used for all outbound links)

- Firebase Dynamic Links (used in mobile apps)

These services are useful for social media, messaging, QR codes, and marketing campaigns. Despite appearing simple, building a scalable URL shortener requires handling billions of redirects, ensuring high availability, minimizing latency, and efficiently managing storage.

Functional Requirements

A URL shortener should provide the ability to convert long URLs into short and compact identifiers that can be easily shared. The main functional requirements include:

-

Create a unique short URL for a given long URL

- Accepts a long URL and returns a unique shortened identifier.

- Optional features may include:

- Custom alias (e.g.,

/my-linkinstead of a random ID) - Expiration time so that shortened links auto-expire

- Custom alias (e.g.,

-

Redirect from short URL to long URL

- When a user accesses the short URL, the system should redirect them to the original URL with minimal latency.

Out of Scope (for this design):

- Analytics, such as:

- Click counts

- Traffic source tracking

- Geographic or device analytics

Non-Functional Requirements

Beyond basic functionality, the system must satisfy various quality attributes:

-

Consistency Model

- Eventual consistency is acceptable for writes (as per CAP theorem).

-

High Availability

- The service should handle failures gracefully and continue serving redirects.

-

Low Latency

- Redirects should be very fast since they are user-facing.

- Typical target: ~200ms or less.

-

Scalability

- Should support large traffic volumes.

- 100 million Daily Active Users (DAU)

- 10 billion redirect requests per day

Entities

The essential conceptual data entities include:

- User Represents an authenticated user who may create or manage short links. (Optional in a public service.)

- LongUrl Stores the original, full-length URL submitted by a user.

- ShortUrl

Stores the shortened identifier and metadata such as:

- Creation time

- Expiration time

- Associated user (optional)

- Custom alias flag

API Design

The external interface can be exposed via simple RESTful APIs.

Create Short URL

POST /urls -> 201 Created

Content-Type: application/json

{

"longUrl": "https://www.example.com/very/long/link",

"alias": "custom-name", // optional

"expirationTime": "2025-01-01" // optional

}

-

Returns metadata including the generated short URL.

-

Server generates a unique slug if alias is not provided.

Redirect Short URL

GET {"{"}shortUrl {"}"} -> redirecting to long url

-

A 301 status indicates a permanent redirect.

-

A 302 status indicates a temporary redirect.

-

Browser automatically follows the redirect to the target URL.

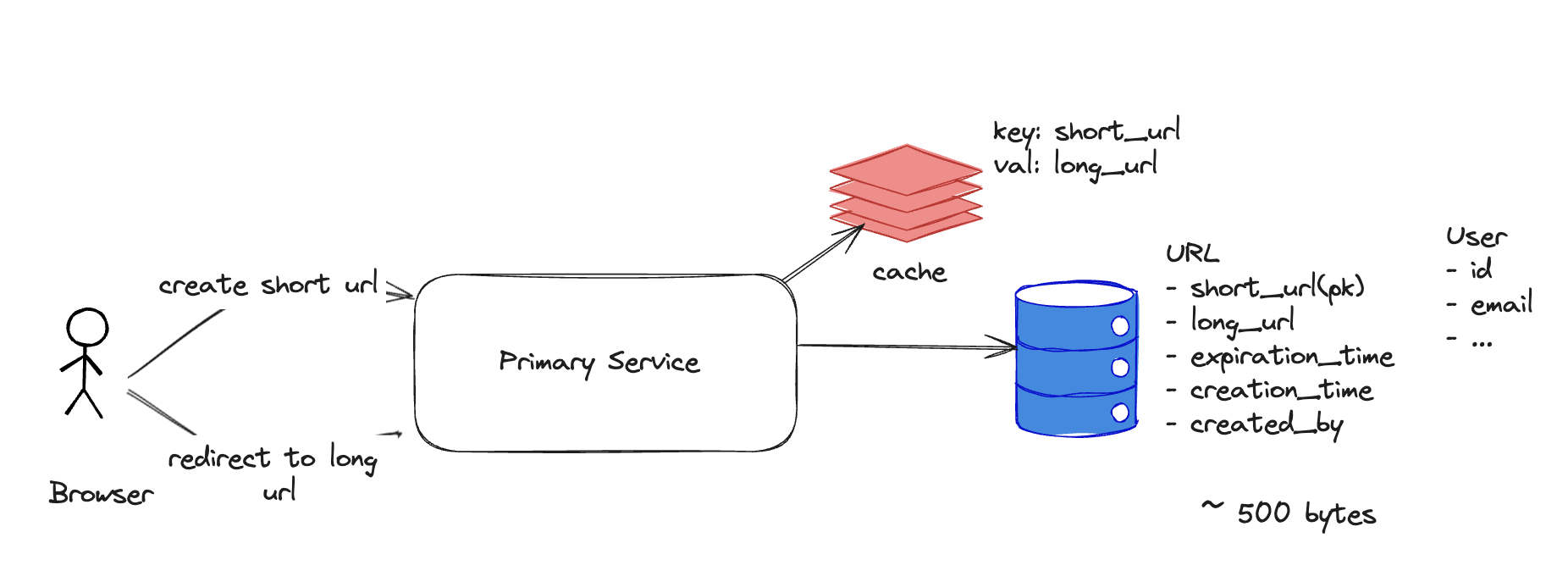

High Level Design

At a very high level, the system consists of:

-

A primary service layer creating short urls and redirecting long urls

-

A Database layer storing URL mappings

-

A Caching layer to speed up frequent redirects

Architectural diagram:

Scale Calculations

To estimate required capacity:

Daily Active Users (DAU): 100 million

Lifetime storage

100M users * 365 days * 10 years ≈ 365 billion URLs

Request Rates

URL creation throughput: 100M / (24h * 3600s) ≈ 1000 TPS (transactions per second)

Redirect throughput: 10B redirects/day ≈ 100k QPS (queries per second)

Storage Consumption

Assuming average metadata size: ~500 bytes per entry

500 bytes * 365B entries ≈ ~200 TB over 10 years

Database Selection

Workload characteristics

- No complex schema or relational joins

- Read-heavy pattern (redirect redirects)

- Eventual consistency acceptable

SQL databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL):

- ✔ Strong consistency

- ❌ May struggle at large scale without sharding

NoSQL databases (DynamoDB, Cassandra):

- ✔ Horizontal scalability

- ✔ Flexible schema

- ✔ High throughput

Conclusion:

NoSQL is typically preferred for large-scale URL redirect systems.

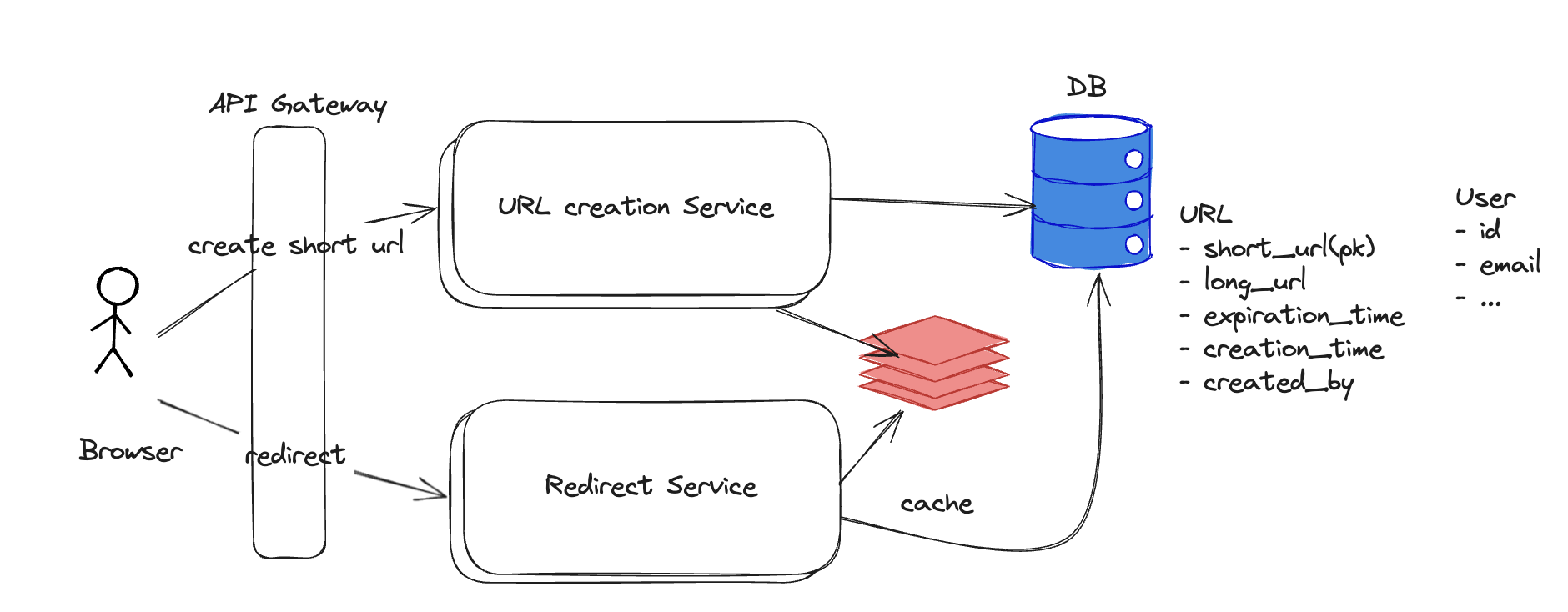

Service Decomposition: URL Creation vs Redirect Service

In large-scale URL shortening systems, it is common to split the architecture into two primary services:

- URL Creation Service

- Redirect Service

This decomposition is not accidental — it addresses performance, scaling, consistency, and cost concerns.

1. Different Workload Characteristics

URL Creation

- Low QPS (e.g., hundreds or thousands per second)

- Write-heavy (insert records + metadata)

- Latency is important but not ultra-critical

- Requires validation, authentication, rate limiting, etc.

Redirect

- Extremely high QPS (could be millions or more per second)

- Read-heavy (lookup + redirect)

- Must be extremely low latency (sub-10ms ideally)

- Often unauthenticated public traffic

By separating these, each can scale according to its unique access pattern instead of over-provisioning a single monolith.

2. Independent Scaling & Cost Optimization

Redirect traffic is massive. If both workloads lived in a monolith:

- Scaling to support redirect QPS forces scaling for creation logic too

- Drives up compute + network costs unnecessarily

With decomposition:

- Redirect Service can use cheap, horizontally scalable caching layers (CDN, Redis, memory caching)

- URL Creation Service runs smaller since it sees minimal traffic

Result: better cost efficiency + operational flexibility.

3. Separation of Critical Paths & Latency

Redirects define the latency SLA of the product:

- Users expect instant page loads

- Adding synchronous metadata writes or validation would slow it down

- Caching can push latency down to microseconds or edge-level delivery

Meanwhile, URL creation can afford minor overhead since it's not in the request hot-path of end users.

4. Different Consistency Requirements

| Concern | Creation Service | Redirect Service |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Strong (writes must persist) | Eventual is OK (new URLs may take time to propagate) |

| Storage | Persistent DB | Cache + in-memory + DB fallback |

| Validation | High | Minimal |

| Authentication | Yes | Mostly No |

This aligns with typical distributed system strategies:

- Write path → stronger guarantees

- Read path → optimized & cached

5. Deployment & Infra Flexibility

By splitting the services, we gain deployment advantages:

- Redirect service can be deployed across CDN edges, close to users

- Creation service can live behind private APIs with stronger auth

- Database writes can be centralized

- DB reads for redirect can be replicated globally

This enables:

- Geo-distributed read replicas

- Edge caching

- Reduced cross-region latency

In short: URL Creation writes data reliably, Redirect reads it fast — these are fundamentally different jobs, so they deserve fundamentally different services.

How to Decide the Short URL Size?

To prevent collisions, we need to support roughly 365 billion short URLs over the lifetime of the system.

We will explore possible character set sizes and URL lengths:

Base-10 (digits only)

10^6 ≈ 1 million combinations (considering 6 char short url)

10^7 ≈ 10 million combinations (considering 7 char short url)

➡️ Way too small compared to hundreds of billions.

Base-62 (0–9, A–Z, a–z)

62^6 = 56 billion (considering 6 char short url)

62^7 = 3.52 trillion (considering 7 char short url)

Hence Base-62 encoding is a popular choice with 7 character short urls.

How to Create a Short URL

There are multiple techniques to generate a short identifier (slug) from a long URL. Each technique has different trade-offs around uniqueness, collisions, and operational overhead.

-

Random 7-character Base62 key

- The system generates a random key of fixed length (e.g., 7 characters).

- Characters are selected from a Base62 set:

0-9,A-Z,a-z. - This provides a large key space (

62^7 ≈ 3.52 trillion), making collisions unlikely. - Requires collision detection logic (e.g., retry if generated key already exists).

-

Hashing approach

- Compute a hash of the long URL (e.g., SHA-256, MD5).

- Take a subset of the hash bits and Base62-encode them.

- Advantages:

- Same long URL always produces the same short URL (idempotent).

- Disadvantages:

- Hash collisions still possible and must be handled.

- Full hash values are too long, so truncation is required.

-

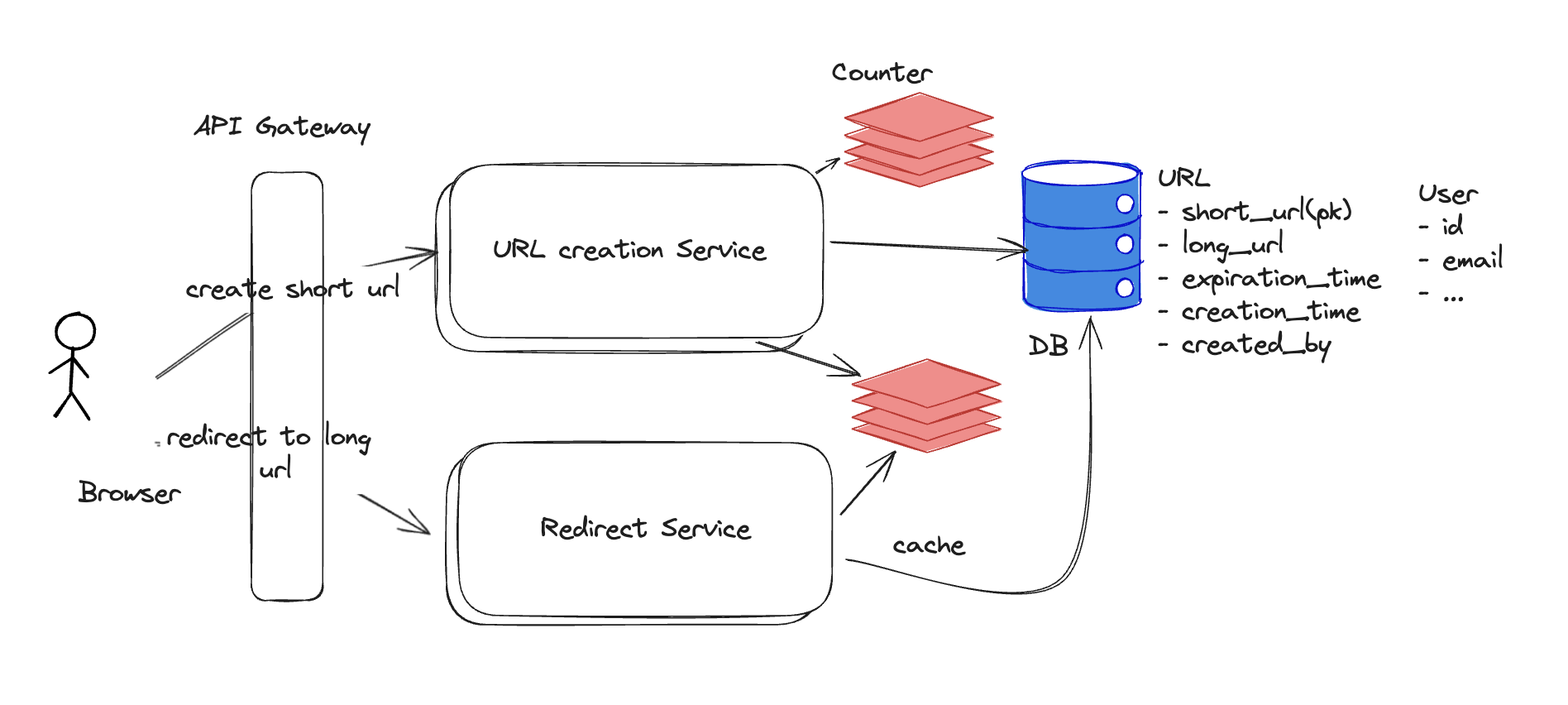

Counter-based approach

- Maintain a global incrementing counter.

- For each new URL, increment the counter and Base62-encode the integer value.

- Guarantees uniqueness without collision checks.

- Commonly used in distributed systems when combined with sharded counters.

| Method | Collision Risk | Scalability | Predictability | Ease of Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Base62 | Low (requires collision check) | Good | Medium | Easy |

| Hash-based (URL → Hash → Base62) | Medium (truncation collisions possible) | Good | High (same URL → same key) | Medium |

| Counter + Base62 Encoding | None (unique increment) | Good with sharding | Full (sequence-based) | Medium |

| Distributed ID (Snowflake) | None | Excellent | Medium (time + machine + sequence) | Hard |

What Type of DB to Use for the Counter?

If using a counter-based URL generation strategy, you need a datastore that can safely store and increment the counter. Options include:

SQL Databases

- Provides

AUTO_INCREMENT(MySQL) orSEQUENCE(PostgreSQL). - Advantages:

- Simple to set up and reason about.

- Strong consistency and ACID guarantees.

- Disadvantages:

- Harder to horizontally scale for very high write throughput.

- Write contention can become a bottleneck at large scale.

NoSQL Databases (e.g., Cassandra, DynamoDB)

- Support distributed storage and high write throughput.

- Advantages:

- Horizontally scalable architecture.

- Good fit for distributed workloads.

- Disadvantages:

- No built-in auto-increment.

- Increment logic must be implemented manually.

- Eventual consistency may lead to counter conflicts if not carefully managed.

Redis

- Provides

INCRandINCRBYatomic operations. - Advantages:

- Extremely fast (in-memory).

- Atomic increments ensure uniqueness without races.

- Can be sharded for scalability.

- Disadvantages:

- In-memory storage means durability must be configured (e.g., AOF snapshots).

- Requires handling for failover to avoid single point of failure.

Redis is often used for short-URL counters because it provides atomic increments, low-latency, high-throughput number generation with a simple model that maps cleanly to Base62 encoding

Redis as a Single Point of Failure

If we rely on Redis as the only component responsible for generating and storing counters, it becomes a single point of failure.

If that Redis instance crashes, becomes unavailable, or experiences data loss, the entire URL generation workflow is affected.

In the worst case, the system would stop generating new short URLs until Redis is restored.

Mitigation Strategy: Sharded Counter Space

One common approach is to avoid having a single global counter and instead shard the counter space across multiple Redis servers.

Each Redis instance manages a dedicated integer range:

Server 1 → 0 – 1,000,000

Server 2 → 1,000,000 – 2,000,000

Server 3 → 2,000,000 – 3,000,000 and so on.

With this approach:

- If Server 1 fails, only the range

0 → 1Mis temporarily unavailable - Other servers continue issuing IDs from their ranges

- No global lock/contention on a single instance

- New shards can be added by allocating new ranges

Redis Counter Sharding Architecture

- Id Shard #1 is down → cannot issue IDs in range

0–1M - Shard #2 and #3 continue serving requests

- Application remains partially operational

Operational Considerations

Sharding improves resilience, but introduces new responsibilities:

- Must track which ranges are allocated and which are free

- Risk of range exhaustion (a shard may run out of numbers)

- Assigning new Counter Ranges to servers

- Need graceful handover if a shard fails mid-range

- Client/service logic must decide which shard to ask for the next ID